Neri Oxman and the Anthropocene

Ella Rosenblatt

Ella (she/they) will graduate from Brown University this spring with a dual degree in the History of Art and Architecture and Science, Technology, and Society (focusing on linguistics and art/writing practice). Beyond studying the intersections of art, design, science, and the digital, Ella loves to create and design herself, mentors young art students at New Urban Arts, and edits several publications. She hopes to continue her creative practices and to teach in the future—and to learn as many languages as she can.

Introduction

Centered in a bright white hall at MoMA, Neri Oxman’s totem-like Aguahoja extends toward the high ceiling, webbed and shaped like two symmetrical insect wings cupped into a cocoon shape (Figure 1). The towering structure resembles an almond shaped shell standing on its point, with a sliver of an opening on one side that shows it is hollow. Its faces are webbed with white veins, filled in between with brown, textured membranes. At once it mimics biological structures enough to be recognized as related to nature, but it also does not model itself on anything particular in nature. Nothing else stands in the MoMA space. The only other elements of the exhibition are a series of large artefacts arranged to fill the adjacent wall (Figure 2). Their gradient of earthy, “natural-looking” brown hues match the colors of Aguahoja’s membranes. The effect is scientific, thorough, taxonomical, even whimsical. Yet at first glance, the collection of objects and structures seems esoteric, provoking curiosity about what materials compose them and how they were produced, along with questions about whether this is science, design, art, or something collected from and produced by nature, rather than human beings. What are these objects and how were they created?

Figure 1

Figure 2

Aguahoja is one of Oxman’s many projects in the practice she terms “material ecology.” Based at MIT, she works with a team called the Mediated Matter Group. Their lab-based design work brings together an interdisciplinary group of researchers, designers, and architects to create unique material technologies and processes, which produce prototypical objects like Aguahoja using biomatter, biological organisms themselves, computation, and scientific experimentation. Oxman and her team’s work has been exhibited in high profile art institutions like MoMA, and she has received extensive media attention. Her work draws on the late 20th century intellectual developments of cybernetics, systems theory, and the beginnings of an environmentalism inspired approach to design and art, particularly in Italy and the United States, that foregrounds critical and ecological consciousness in reaction against mass consumerism and Modernism. Theorists and designers of those movements imagined and reconfigured environments to envision a better future. Today, rather than simply imagining a future, Oxman and the Mediated Matter Group perform, and thus concretize, a provisional model of a design process that reconfigures human and non-human relationships. Her work reflects the increased urgency of environmental issues in the 20th century, and how design and art can function as a laboratory for solutions to problems that characterize the era controversially called “the Anthropocene.” These include anthropocentrism and humanist exceptionalism, extractive relationships with matter and materials, and imagining the future amid dominant doomsday narratives of crisis. Oxman takes a distinctly positive outlook, envisioning her work as a designer as both a visionary and orchestrator of the future. Thus, she models human relationships with matter and nonhuman species that reflect zoe-egalitarianism and strive toward non-extractive logics. By manifesting these concepts in the built environment, in academia, and concretely in the world, Oxman hopes to contribute equitable and responsible inter-zoe relationships, that is between matter, machinery, nonhuman species, and humans, enacting a better future today.

Material Ecology, Discourses of the Anthropocene, and the Posthuman “Zoe”

Oxman’s “material ecology” concept of design is clearly informed by theories and research of the “climate crisis” and the conditions of the Anthropocene. She defined the term

“material ecology” in 2010 as

an emerging field in design denoting informed relations between products, buildings, systems, and their environment... Defined as the study and design of products and processes integrating environmentally aware computational form-generation and digital fabrication, the field operates at the intersection of Biology, Materials Science & Engineering, and Computer Science with emphasis on environmentally informed digital design and fabrication.

“Environmentally aware” material ecology arises from increasing awareness and urgency of the crises that characterize the Anthropocene. The Mediated Matter Group draws on the many disciplines in which members have expertise to execute cutting-edge research, creating engineering technologies that employ digital and mathematical modeling, biochemical knowledge, and creative design thinking to envision unique processes specific to the materials they use. By “material,” they refer to the group’s foregrounding of material exploration in design. They begin with researching materials, later allowing them to shape the form of a structure as much as the researchers shape it. This upends the more traditional notion of design, which begins with the form and ends with choosing a material to execute it. The use of “ecology” invokes ecological and systems-based thinking, as well as an interest in environmental concerns. “Ecology” places materials within a system or context, and it brings together all the elements of that context, from matter to complex organisms to weather conditions.

Oxman explains this approach as bringing together not only humans, their environment, and animals, but also material objects and matter within ecological systems. This leads to her design work, which treats materials and matter as peers with nonhuman species, humans, and all that is vital or self-organizing. Rosi Braidotti, a philosopher and scholar of posthumanism and critical theory suggests use of the term “zoe”, which she defines as “The wider scope of animal and non-human life” and “the non-human, vital force of Life.” Braidotti describes the reconfigured relationship of egalitarianism between all entities with a “Life” or “vital” force as “zoe-centered egalitarianism,” providing a non-dualistic, non-hierarchical term for all species and matter. This notion of “zoe-centered egalitarianism” is at the heart of what Oxman tries to do with material ecology: to model and illustrate reconfigured relationships between humans; nonhuman species such as silkworms, bees, or microbes; and matter including robots, computers, and the structures that house it all. Everything fits within a system with everything else, and the cybernetic notion of feedback loops and chain reactions between elements of the system inherently implies an ethics of responsibility not to harm other elements of the system, and thus consciousness of one’s actions.

Oxman’s interest in ecology and systems responds to and draws on discussion of the term “Anthropocene” to denote the current geological era, including discussions of the Anthropocene focusing on human relationships with material. For some researchers and historians, the Anthropocene is already a fixed, accepted term for the contemporary geological moment; for others, the term remains in flux and presents problems of definition and etymology. In 2006, Dutch chemist Paul J. Crutzen “suggested delineating the Anthropocene as an epoch in which humans have become ‘one of the great forces of nature’,” prompting many others to research the beginning point of this new geological epoch. Scientists have proposed many possible historical moments or “golden spikes” that might bookend this era including “the spread of agriculture, the invention of the steam engine, the Great Acceleration, and the first nuclear detonation.” Siri Veland and Amanda H. Lynch, environmental scientists at Brown University, challenge the notion of identifying a single definition or period of the Anthropocene because those perspectives often “follow traditions of linear and authoritarian historical accounts, and prevent discovering epistemes of human-environment interactions that are open for coexistence.” This perspective of allowing multiple narratives to coexist encourages active discourse; they pragmatically suggest that this will encourage continued discussion, narratives, and research into the issue.

Taking a more critical perspective, in A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None, geologist and critical theorist Kathryn Yusoff questions the origin of the Anthropocene, drawing on Black Feminist theory and geology and describing the metaphorical resonances of resource or matter extraction in parallel to human slave exploitation in the history of racial injustice. She problematizes the Westernness and Whiteness of geology and its scientific “objectivity,” which in turn undercuts the authority of a geologically-rooted term such as the Anthropocene. Kyle Whyte, an Indigenous scholar whose work centers on communities and the environment, questions the overarching narrative and language of “crisis” surrounding the Anthropocene, arguing that some people—specifically Indigenous populations—have already suffered similar conditions due to colonialism and historical and continued violence. Since large-scale crisis has already occurred for those who have encountered such violence, doomsday narratives and invoking the climate “crisis” makes clear that those narratives come from voices privileged enough to not already exist in circumstances of crisis. The coexistence of staunch critiques of the term Anthropocene and set acceptance of it as the title of this period imbue the term with conceptual and historical weight. For the purposes of addressing Oxman’s work in the current moment in time, it is useful to employ the term Anthropocene to index all the climate, environment, and socioeconomic issues it entails. Invoking this term also enters her work into the discourse surrounding its history that illuminates the limitations of calling the current moment a climate “crisis” or universally attributing blame for shifts in climate versus attributing it to concentrated, harmful populations.

Oxman’s Background and Design Histories

Both Oxman’s personal history and the history of environmental art and design in the United States and Italy during the latter half of the 20th century contextualize the development of her specific approach. Designer, architect, philosopher, professor, researcher: Neri Oxman’s career defies disciplinary boundaries and reflects her exposure to seemingly disparate fields in her childhood and education. Oxman’s upbringing established her consciousness of potential relationships between nature and architecture, growth and computation. She was born in 1976 in Haifa, Israel, where she had an idyllic youth. Her parents, Rivka and Robert Oxman, are both architects and scholars whose work notably deals with the relationship between design and computation. Oxman describes her time in Haifa as a blend of exposures: to nature in the mountains and sea of Haifa and her grandmother’s garden; and to her parents’ architectural and structural work, which was informed by Bauhaus design. In sharp contrast with that childhood, Oxman entered the Israeli military at 18 where she “saw the extremes of the human spirit.” Exposure to military technology, human suffering, and war form a part of Oxman’s background, and perhaps this history underlies her humanitarian drive.

Oxman’s education likewise drew from multiple fields in the form of academic disciplines. She began medical school, but shifted partway through to architecture training at the Technion in Tel Aviv and the Architectural Association in London. Oxman’s architectural and design work remains clearly informed by her early scientific and medical studies, however. In addition, her early exposure to Bauhaus design influenced her later approach to design and interest in avant-garde strategies, as well as design based upon conceptual and theoretical ideology. Founded by Walter Gropius in 1919, the Bauhaus’ design philosophy, which emphasized exploration of material and the usage of new technologies, has continued to be influential on 20th century design. Gropius and subsequent designers and artists critiqued design practices shaped by modes of mass production and industrial processes.

Oxman prefaces many discussions of her own design work saying that the world of design has been controlled by the demands of mass consumerism and capitalism since its advent. This has established the paradigm of designers thinking of objects as assemblies of discrete parts with different materials, which she considers a problem: that design thinking and choices have been controlled by mass production and its imperatives. Oxman’s design approach attempts to do what she imagines is the opposite: to design provisional material processes that grow, rather than assemble, and to treat material as a collaborator in designed processes specific to that matter, which is necessarily embedded in ecological systems that cycle through different manifestations in the world. Her approach thus does not imagine material as an extracted, harvested, or mined raw resource with which to execute human ideas, but rather sees it as necessarily embedded in an ecological system and the starting point for process. The way that she allows the membranes Aguahoja produces to dry in the bend configuration that they do, rather than flat as they are printed, exemplifies this response to material in the design process.

There are many other schools of design that inform Oxman’s perspective and similarly respond to the problems of Modernist design and the Bauhaus’ original principles. Italian critical design of the 1960s and 1970s saw design as a realm of speculation about the future and included designers creating objects or ideas that rejected mass capitalistic systems. The 1972 MoMA exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape brought together many examples of Italian design, which was internationally influential. Described as a “micromodel in which a wide range of the possibilities, limitations, and critical issues of contemporary design are brought into sharp focus,” Italian Design’s prominence at the time allowed the exhibition to address central concerns of the later 20th century in design: mass production and ubiquity of design objects, design’s role in domestic spaces, design of environment or space, adaptability despite mass production, and design’s social role. Many Italian designers conceived of their work as uniquely conceptual, versus that of other countries or regions, seeing design as a mode of shaping people’s environments while also promoting ideas embedded in design. Giulio Carlo

Argan, who was the chair of the history of modern art at the University of Rome at the time of Italy: The New Domestic Landscape, commented: “The final goal is to train people in the aesthetic interpretation of their material environment, so that they can recover their faculties of independent judgment and evaluation, which a consumer society tends to stifle by encouraging indiscriminate, prodigal buying.” The anti-consumerist sentiment also emphasizes the aesthetics of environment and sensitivity of the public to them. Argan asserts that Italian design is more similar to art and involves a semblance of “research:” design for Italians working at this time is not “looked upon as a structural principle of objective reality, but rather as a principle of awareness.” This notion of design as consciousness-raising, conceptually driven, research-based, speculative, and propositional all aligns with both Oxman’s practice and more recent movements to de-commodify design and render the field conceptually rigorous and essential to solving world problems.

Across the Atlantic, Victor Papanek “was one of the twentieth century’s most influential pioneers of a socially and ecologically oriented approach to design beginning in the 1960s” and wrote “Design for Real Worlds” in 1971, in which he advocates for “inclusion, social justice, and sustainability” in design. Papanek, who is clearly a predecessor of contemporary, socially- and critically-engaged designers like Oxman, critiques consumerism and created projects that involved sensorial experiences and variable, flexible functions of objects. He demonstrates a “commitment to the needs of what was then known as the ‘Third World,’ ecology, sustainability, and ‘making’ culture – creation and production using one’s own resources,” all of which reflect parallel movements today as designers commit to intersectional and ecological ideology that completely reconfigure the role of the designer in the world. Instead of the past notion of the designer simply as creator of objects or creator of the parts with which they are made, shifted senses of responsibility and the paradigmatic shift away from consumer-driven design prompt designers to see their work as political, programmatic, and essential to imagining and building better futures for all humans and nonhuman entities. Papanek’s other contribution is the notion of nature as being equivalent to design, and that this inherently involves the computational idea of DNA as a code, which parallel’s Oxman’s reverence and reference of nature.

During the same period, art collectives such as Pulsa, “self described as researchers in programmed environments” similarly bridged scientific practice, art, and design methodology to create multimedia installation projects using sound and video. Driven by a desire to expose underlying systems in the environment through aesthetic experience, they created projects like “a computer-programmed environment of light and sound for which ten electronic and related companies have given or lent the necessary equipment requested by the artists” in the MoMA sculpture garden in 1969. As art historian T. J. Demos puts it, “Pulsa did accomplish important work geared towards de-idealising nature and disarticulating the environment to the degree that nature’s separation from social, political and technological processes was impossible to maintain.” Clearly Pulsa and Oxman demonstrate similar drives to break down nature-culture categorical divides. This work exemplifies art conceptually inspired by systems and ecological thinking that came about around fifty years ago, whose lineage now includes the Mediated Matter Group.

Recent design movements build off of Italian and American anti-modernist, ecological, and systems-based practices with new urgency and language to articulate their ideologies, which stem from social and environmental justice movements and theory. Those recent movements include what is called Critical and Speculative Design, which reacts against modernist design and education, expresses frustration with the culture of mass consumerism, embraces rapid and drastic technological change, and uses the language of networks and systems. Such work has been shown in many high profile exhibitions, including the 2019 Broken Nature: XXII Triennale Di Milano which centered intersectionality and considered the limitations of “ ‘Organic,’ ‘green,’ ‘environmental,’ and “sustainable’ ” as “buzzwords that have been applied in earnest to design” as well as other ethics-invoking terminology. Broken Nature highlighted works of art and design “encouraging new behaviors using objects...as prompts and foils,” including interdisciplinary and global collaborations.18 The exhibition's constructive and positive ideology mirrors that of Oxman, describing its aim “to reconsider our relationship with nature beyond pious deference and inconclusive anxiety and instead move toward a more constructive sense of indebtedness to the environment.” This exhibition illustrates the blending of social justice with ethically-focused, critical, and speculative design to address broad problems ranging from climate change causes such as pollution to social and literal mobility to accessibility of many types. This exhibition embodied contemporary cutting-edge design that opposes the still extant school of design whose drive is consumer products and manipulation of people, the environment, and matter to serve the economic system of capitalism. Not only do Oxman and her contemporaries see the realm of design as essential to remedying the ill effects of climate change, finding solutions to problems, and improving human relationships with other entities, but they also contrast with the dominant negative narrative of this moment in time and the Anthropocene, with their own constructive, positive visions and ideas.

Aguahoja: Modeling Zoe and Subverting Extractive Logic Through Material Ecology

Returning to Aguahoja, we can more closely examine Oxman’s treatment of matter in the work as well as her team’s design process. Yusoff’s analysis of matter and the Anthropocene in relation to geology, histories of extraction, and racial injustice provides language to understand Oxman’s subversion of extractive logic and treatment of matter from a zoe-egalitarian perspective. In A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None, Yusoff asserts that the grammar of geology—stratification of layers, matter as the source for industrial material—is tied to the history of colonialism and slavery, which metaphorically align with the “extractive logic” of stratified hierarchies of people and exploitation of de-humanized resources, whether matter or slaves. Divisions and subsequent hierarchies of matter allow for the subjugation of some below others, as Yusoff describes, as it pertains to race, saying, “racialization belongs to a material categorization of the division of matter (corporeal and mineralogical) into active and inert.” Braidotti’s zoe remedies the division of matter into “active and inert” categories that Yusoff describes, opting for monism over division. In the conditions of the Anthropocene—in which humans and non-humans are viscerally experiencing the impacts of anthropocentrism, mass industry, and the paradigm of progress—division and lack of consideration of egalitarianism has the potential to lead to extinction for all sorts of matter, including certain resources. Only reshaping these networks of relationships in the broader world system can remedy exploitative and thus harmful relationships embedded within it. Yusoff diagnoses this problem, and Braidotti’s zoe embodied and modeled by Oxman’s material ecology contributes to a solution.

A new constructive notion of matter in relation to the human—that is, a relationship of monism that encompasses all that is vital and self-organizing—proposes a way to eliminate the hierarchies that Yusoff critiques and argues are implicit in all geological logics. Whereas the original Western geologists and geographers saw matter and the earth as purely sources of material to serve economic systems of consumerism, both the provisional nature of Oxman’s work and thus its anti-consumerist logic, as well as the attention Oxman pays to the materials she uses—their histories, tendencies, and properties—illustrate an alternative mode of designing that upends extractive logics of the past in favor of zoe-egalitarianism and ecological systems-aware logics of creation, and embedded in nature.

Aguahoja encompasses its process of creation, which entailed long-term research, material and engineering experiments and its conceptual inception, as well as the artifacts of that process hung across MoMA’s wall and the Aguahoja pavilion, which towers in the center of the gallery. Sculptural prototypes result from material experimentation and display side-by-side with data. That data is visual, forming dynamic surface textures and patterns (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4), multicolor gradients, arrays and series of graphs or iterative prototypes. By de-centering design products or objects in favor of designing processes and technologies, becoming intimately familiar with the materials involved in her work through research, treating matter as vital, and by imagining the objects and matter as embedded within a system or ecological environment, Oxman carves out an alternative mode of designing to extractive logics of the past that Yusoff identifies.

Figure 3

Figure 4

De-centering the object reflects Oxman’s anti-consumerism, favoring modeling and producing the processes of design rather than the objects. Oxman’s work consists of that documentation of her team’s process, and not a single “final product.” Thus, Oxman subverts the traditional idea of the design object, or the finished sculpture, valuing process and prototype above the product. The work is her team’s iterations, collaboration, and transparent documentation of it. Each of the Aguahoja artifacts is not replicated or mass produced. They exist forever as provisional and unique objects to illustrate a process. Likewise, the pavilion is not intended for replication or to be a model of another structure. It is experimental, the result of an explorative process. The numerous artifacts show that there was not a set “design” or goal in mind for the team, but rather that they were inquisitive about how to generate structure with materials that could be broken down by water. Thus, objects in material ecology are significant only as remnants of process or ways of conveying concepts, signaling devices. They serve no function and are not meant to be useful or industrially produced.

Aguahoja is rather the design of a process that emulates the natural process of growth, rather than the assembly process typical of mass production. Oxman describes Aguahoja as “an exploration of Nature’s design space.” Oxman terms Aguahoja an exercise in synthetic biology, or actually synthesizing natural processes and thus exploring nature’s ways of designing.23 Aguahoja reflects the notion of synthetic biology less than some of Oxman’s work, where nonhuman zoe such as silkworms spin structures, or bacteria produce melanin coloration of walls, and so on. For Aguahoja, biological, water-soluble materials are 3D printed (Figure 5) using a unique technology for 3D printing water-based biomatter that Oxman and the Mediated Matter Group produce themselves. This process does entail the use of biological materials and replicates processes of additive construction, akin to “growth,” yet it does not perfectly synthesize the untouched processes of growth for which these materials are used in nature. By calling it an “exploration,” Oxman stresses that the process is provisional and experimental, rather than definitive and intended for some specific goal or production line. Yet the notion of this process being the central production of the designer and design team does upend previous ideas of the object as central to design. In addition, this process does take steps toward a growth rather than assembly approach, and Oxman’s other projects reflect even closer semblances of true synthetic biology as applied to design work as well. The ideal as Oxman puts it is to bring “Nature’s material intelligence” into design, fabrication, and environments.

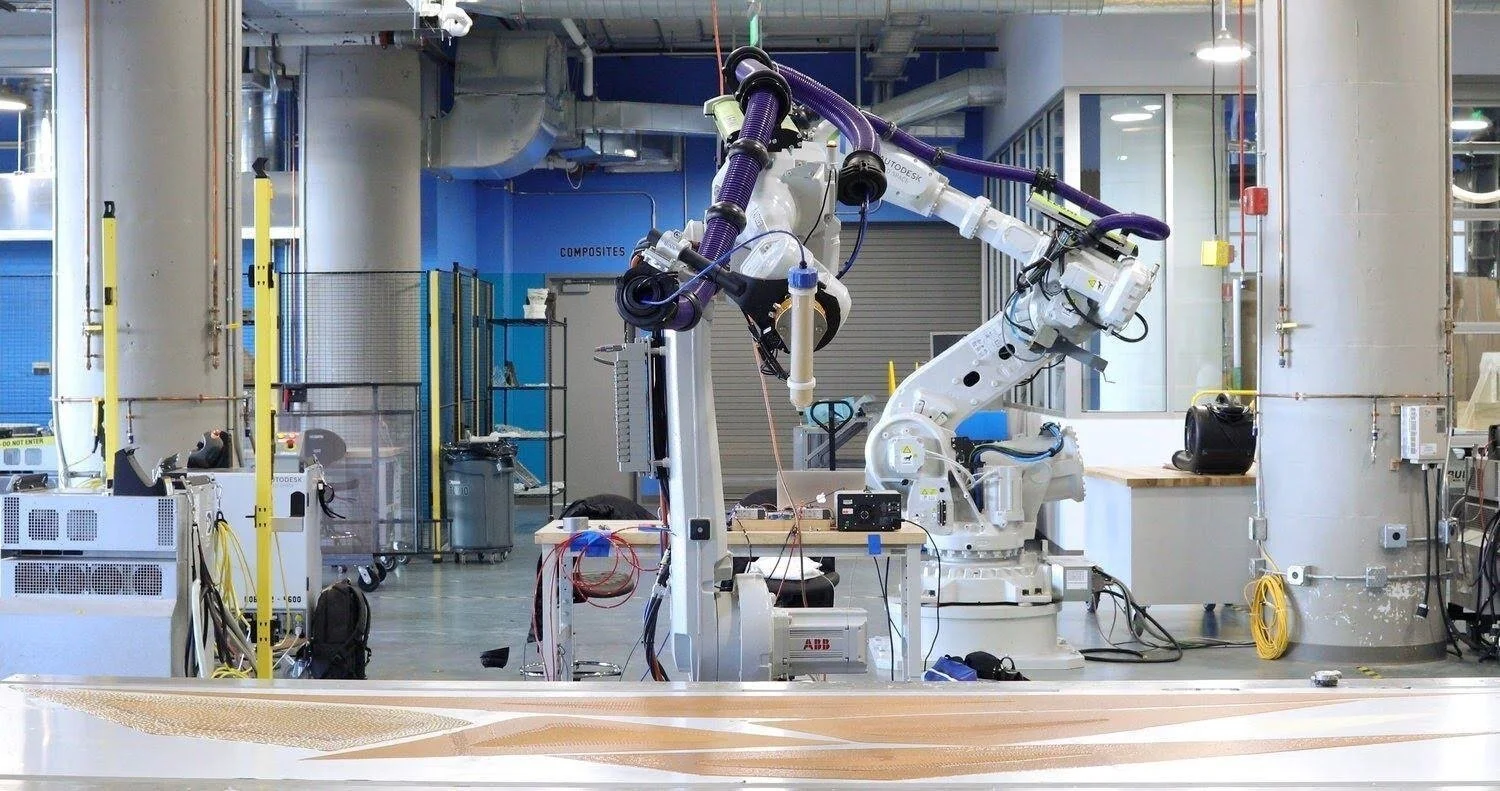

These objects are merely artifacts of a collaborative process between machines, humans, and non-human zoe. Donna Haraway’s notions of sympoesis and autopoesis provide a useful framework to describe collaboration between humans and nonhuman zoe. Haraway argues that “nothing makes itself; nothing is really autopoietic or self-organizing.” Oxman describes how the artifacts bend as they are exposed to air and solidify after being printed flat, demonstrating how the materials co-author the final form. They have their own tendencies and organization, which shapes the ultimate artifacts. In addition, the Mediated Matter Group also uses computation and digital tools to model and visualize the chemical and engineering processes, and robotic additive manufacturing or 3D printing to form the artifacts of the process they ultimately create (Figures 6, 7). Those technological tools also shape and influence the process. At the outset, the entire human approach to forming material begins with knowledge of the capabilities of machines and knowledge of the materials, and that foreknowledge also influences the creating process. This exemplifies a process of creating-with or sympoesis, to draw from Haraway: a collaboration between zoe that thus equalizes different entities.

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Oxman imagines design that can immediately embed its artifacts and processes within ecological cycles of matter. Rather than the conventional notion of recycling that involves heavy processing of human-engineered, non-biodegradable materials, Oxman wants to create processes to allow humans to grow aspects of the environment out of materials that already fit into its existing life and death cycles. This research centers around the problem of the built environment being populated with single-use objects that later populate landfills and require rapid resource extraction from the Earth to be made. Instead, Oxman imagines matter that embeds itself within its environment in a responsive, rather than, impositional way. The artifacts are thought of as responsive to their environments because their structural strength depends on the load-bearing needs of localized points on the overall surface, variable material properties that are calculated and envisioned with computer technology. The Aguahoja pavilion and artifacts are also responsive to heat and humidity in their surroundings. The way that they are responsive both structurally and atmospherically to the environment reflects Oxman’s understanding of how naturally-occurring entities respond to their environments: the minerals in stone cycle through streams, enter water systems, nourish bodies, conglomerate into larger rocks, etc. Oxman intends the Mediated Matter Group’s artifacts to do the same. The artifacts are ultimately thought of as “biodegradable composites” of biomatter, able to enter water-based ecological cycles of use and reuse of matter in the environment. These objects not only are conceived of as genuinely biodegradable, hewn from the same materials that biological entities are, but they are also thought of as radically responsive to the environment, and thus able to embed in the ecological system in a way that single-use materials and objects cannot, rather accumulating cancerously in mounds or islands in the ocean.

Aguahoja does have a shortcoming in its treatment of matter, namely how it derives the matter it does use. For Aguahoja, the group creates “environmentally responsive biocomposite artifacts” from the most abundant materials on our planet—cellulose, chitosan, and pectin.” Those materials are abundant, yet the group does not indicate where exactly they are sourcing the bodies of those substances with which they 3D print for this project. This presents a problem of the potential extraction of these resources in much the same way that Yusoff describes geological extraction of rock, mineral, and ore. However, since Oxman does not intend these materials to be used on mass scales, and she emphasizes their capacity to decompose and enter ecological, water-based systems easily and immediately, this issue may just be a problem with the provisional model of this process. This problem also reveals how this project is not about the objects or the actual project, but rather conveying and concretizing conceptual ideas about vital entities in the world and humans’ relationships with them.

Conclusion

Everyday we encounter, touch, see, and interact with thousands of objects. An onslaught of material and consumer items inhabit and essentially form human environments. These objects carry insidious power, however: powers to pollute, to kill directly or indirectly, to be produced at such volumes so as to cover the surface of the planet. Aguahoja and Neri Oxman’s design work more generally prompts us to question this paradigm of the built environment, one that now shapes and has debatably created the conditions of the Anthropocene era in the past. Following revolutionary thinkers of the late 20th century, working to create art and design that bridges disciplinary boundaries and seriously considers responsibility to environments, natural or social, and its own critical conceptual capacity, Oxman today takes those utopian, speculative ideas and executes them in the concrete realm. Her material ecology work subverts extractive logics of the past in order to illustrate zoe-egalitarianism as well as a model of a new role and mode of working for designers. Amid dominant apocalyptic, doomsday narratives, Oxman takes a positive stance: that design provides opportunities to convey and model new modes of relating to the world around us, that the built or designed world is not necessarily consumer-driven, wasteful, or exploitative, but that designers and design-thinking can contribute to not only imagining, but actually building—or rather, growing—better futures.

Works Cited

“About Italian Design: the Bauhaus School.” About Italian Design: the Bauhaus School, 2006. http://www.aboutitaliandesign.info/bauhaus-school.html.

Ambasz, Emilio. Italy, the New Domestic Landscape: Achievements and Problems of Italian Design; Florence: Centro Di, 1972.

Antonelli, Paola, and Anna Burckhardt. Neri Oxman. Material Ecology. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2020.

Antonelli, Paola, and Ala Tannir. Broken Nature: XXII Triennale Di Milano. Milano: La Triennale di Milano, 2019.

Bateson, Gregory. “Steps to an Ecology of Mind,” 1999.

Braidotti, Rosi. The Posthuman. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2013.

Capra, Fritjof and Pier Luigi Luisi, The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision, Cambridge University Press, 2014

Demos, T.J, Decolonizing Nature, Sternberg Press, 2016.

Demos, T. J. “The Politics of Sustainability: Contemporary Art and Ecology.” In Radical Nature: Art and Architecture for a Changing Planet 1969–2009, published in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name, shown at the Barbican Art Gallery, edited by Francesco Manacorda, 16–30. London: Barbican Art Gallery, 2009. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/3417.

Despret, Vinciane, What Would Animals Say If We Asked the Right Questions? University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Denes, Agnes. The Human Argument: The Writings of Agnes Denes, Edited by Klaus Ottmann. Canada: Spring Publications, Inc, 2008.

Foucault, Michel. “The Order of Things,” 2018. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315660301.

Griffith Winton, Alexandra. “The Bauhaus, 1919–1933.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bauh/hd_bauh.htm (August 2007; last revised October 2016)

Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

Haraway, Donna Jeanne. 2016. Staying with the trouble: making kin in the Chthulucene.

Hiesinger, Kathryn B., Michelle Millar Fisher, Emmet Byrne, López-Pastor Maite Borjabad, Ryan Zoë, Andrew Blauvelt, Juliana Rowen Barton, et al. Designs for Different Futures. Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2019.

Latour, Bruno. “How to make sure Gaia is not a God of Totality? With special attention to Toby Tyrrell’s book On Gaia,” Theory, Culture and Society 34, no. 2–3 (2017): 61–82.

Lewis, S., Maslin, M. Defining the Anthropocene. Nature 519, 171–180 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14258

Maldonado Tomás. Design, Nature, and Revolution: Toward a Critical Ecology. New York: Harper & Row, 1972.

Morton, Timothy, Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. Columbia University Press, 2013.

Morton, Timothy, Being Ecological. Penguin Books, 2018.

Morton, Timothy. Hyperobjects (2013), 1–96. Ebook.

Morton, Timothy. “The Art of Environmental Language,” in Ecology without Nature (2007), 29–78.

Oxman, Neri. “Design at the Intersection of Technology and Biology,” filmed Oct 29 2015. TED Video, 17:32, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CVa_IZVzUoc.

Oxman, Neri. “Neri Oxman: On Designing Form.” Poptech, 20:42, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=txl4QR0GDnU.

Oxman, Neri, interview with Spencer Bailey, “Time Sensitive Podcast,” The Slow Down, podcast audio, August 1, 2019. https://timesensitive.fm/episode/neri-oxman-extraordinary-visions-biological-age/

Oxman, Neri. NERI OXMAN, 2020. https://oxman.com/

Oxman, Neri et al. MEDIATED MATTER, 2020. https://mediatedmattergroup.com/

Popova, Maria. “Buckminster Fuller's Manifesto for the Genius of Generalists.” Brain Pickings, July 12, 2016. https://www.brainpickings.org/2013/03/08/buckminster-fuller-synergetics/. Raymond, Arlo. ‘Media Ecology’, Radical Software, 1/3, 1971, p. 19; cited in William Kaizen in ‘Steps to an Ecology of Communication: Radical Software, Dan Graham, and the Legacy of Gregory Bateson’, Art Journal, Fall 2008, p. 87.

MoMA Press release No. 164. “SPECIAL TO ARCHITECTURAL MAGAZINES AND EDITORS: SPACES EXHIBITIONS AT MUSEUM OF MODERN ART,” 30 December 1969. https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_press-release_333098.pdf?_ga=2.33978721.1172617336.1607390052-1759030607.1606266763

Sagan, Dorion. "CODA.: BEAUTIFUL MONSTERS: TERRA IN THE CYANOCENE." In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, edited by Tsing Anna, Swanson Heather, Gan Elaine, and Bubandt Nils, 169-74. MINNEAPOLIS; LONDON: University of Minnesota Press, 2017. Accessed December 7, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt1qft070.29

Våglund, Linnea, and Leo Fidjeland. “Biosynthetic Futures.” Future Architecture, 2016. https://futurearchitectureplatform.org/news/33/biosynthetic-futures/

Veland, Siri and Amanda H. Lynch, Scaling the Anthropocene: How the stories we tell matter, Geoforum, Volume 72, 2016, Pages 1-5, ISSN 0016-7185.

Whyte, Kyle P. “Indigenous Science (Fiction) for the Anthropocene: Ancestral Dystopias and Fantasies of Climate Change Crises.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 1, no. 1–2 (March 2018): 224–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848618777621.

Wolfe, Cary. “From Dead Meat to Glow-in-the-Dark Bunnies: The Animal Question in Contemporary Art.”

Yusoff, Kathryn. 2018. A billion black Anthropocenes or none.